The first real place west of Brașov is Făgăraș, but our attempt to avoid it altogether didn’t quite work. One minor fuel-level-related marital later, we found the petrol station which had eluded us for the entire stretch of the DN1 between the two cities, and took a subtly different route off the main highway. I’m not going to make any value judgements as to whether our original planned loop would have been a better route or not – but the revised detour certainly got us off the beaten track. Or, indeed, almost off any track altogether… Our target was the monastery of Sambata de Sus – founded by Constantin Brâncoveanu (who we’d already “met” several times), and his burial place (although his body is actually in Bucharest). The monastery’s buried at the foot of some fairly serious mountains, forming the southern border of Transylvania – a wonderful location for some beautiful buildings. Inside one section of the cloisters, there’s a museum of icons painted on glass. We’d seen some of these in the Museum of the Romanian Peasant, back in Bucharest, and wanted to find out a bit more. However, it turned out that we might have done better the other way around… Whilst the selection here was beautifully presented and lit, in a wood-panelled attic, there weren’t actually that many – and very little information. Meanwhile, in the background, the (lay) chap behind the ticket desk at one end of the museum only paused his loud viewing of somewhat anachronistic YouTube music videos to answer his mobile…

Still, as we started to wander back to the van, we were interrupted by a slightly funky rhythmic tapping. A quick look around soon found the source – a monk, circling the church, beating the long wooden board which has been hanging outside every Orthodox church here, as a call to prayer. After a few minutes of this, the bells started to peal, and the evening service began.

Meanwhile, we’d found our way back out to the main road, via a town which looked to be one of the recipients of Ceașescu’s “Systematisation” policies – clearing the villages and housing all the residents in “modern” concrete apartment blocks, to try to level the inequalities between urbanites and the rural peasant. The inevitable result, of course, was a lot of very unhappy people forced to live in an alien environment, and a decrease in agricultural output… Fortunately, the plan was only put into place shortly before the revolution, so relatively few clearances ever happened, and most villages were untouched.

We quickly found the one we were after, Cârța, home to a Dutch-run campsite down a little dirt track from the village centre. The village shop – a steel shipping container, with a window and door cut into one side – was doing thriving business. When Ellie wandered down to get some provisions, she was accosted by an older-looking lady in traditional costume, who seemed determined to have a chat. A certain amount of linguistic confusion reigned, but it started off with pleasantries and asking about age, children etc – then quickly moved on to asking if Ellie would like to take a photo of her, before requesting coffee/cigarettes/money…

There’s also the ruins of a Cistercian abbey in the village – the arches of the cloisters tail off into the shrubbery, but the church remains in use, as does the tall and stand-alone bell tower. There’s a set of steps leading up the tower, just inviting a wander up to survey the landscape. If you should happen to take that invitation up, I’m told that it’s really easy to forget that you’re right in the middle of the bells, and be so busy watching your feet to make sure you don’t fall head-first down the ladder that you promptly head-butt one of the bells. Still, the blood wiped off the bell easily enough.

There’s also the ruins of a Cistercian abbey in the village – the arches of the cloisters tail off into the shrubbery, but the church remains in use, as does the tall and stand-alone bell tower. There’s a set of steps leading up the tower, just inviting a wander up to survey the landscape. If you should happen to take that invitation up, I’m told that it’s really easy to forget that you’re right in the middle of the bells, and be so busy watching your feet to make sure you don’t fall head-first down the ladder that you promptly head-butt one of the bells. Still, the blood wiped off the bell easily enough.

As with so many of the Saxon churchs in Transylvania, the war memorial plaque shows one of the little-known follow-ons from WW2. After the communists took over, the entire working-age Saxon population were deported to Soviet forced labour camps as a reprisal for their connections with Germany. This, of course, ignored completely many having fought against the Nazis… A large proportion of them, of course, never came back – and those that did found most of their property confiscated.

Barely a kilometre or so further up the main road from Cârța, there’s an innocuous-looking side turning for the Trans-Făgărașan Highway. That last word  might be a bit of a stretch, but what a road! Allegedly, Top Gear claimed this was the “world’s best road”. Whilst I’ll treat that with the usual disdain reserved for Clarkson, it is indeed a corker – probably better than the Norwegian Trollstigen. Heading south, you climb back-and-forth up the mountainside, with a tremendous view beneath you as a (Coca-Cola liveried!) cablecar narrowly misses your roof as it makes its own way up. An ever-changing mist just added to the drama whilst we stood in a layby, watching transfixed, as a huge flock of sheep picked their way down what appeared to be a near-vertical rockface, whilst the shepherd sat on the edge of the road nearby idly rolling a ciggy and writing a text message – to his dog, p’raps?

might be a bit of a stretch, but what a road! Allegedly, Top Gear claimed this was the “world’s best road”. Whilst I’ll treat that with the usual disdain reserved for Clarkson, it is indeed a corker – probably better than the Norwegian Trollstigen. Heading south, you climb back-and-forth up the mountainside, with a tremendous view beneath you as a (Coca-Cola liveried!) cablecar narrowly misses your roof as it makes its own way up. An ever-changing mist just added to the drama whilst we stood in a layby, watching transfixed, as a huge flock of sheep picked their way down what appeared to be a near-vertical rockface, whilst the shepherd sat on the edge of the road nearby idly rolling a ciggy and writing a text message – to his dog, p’raps?

The very top of the pass was marked by a tawdry mess of tourist-tat stands, but once past there, the road descended through yet more hairpin bends and sheer drops, before forestry hid the view.

Between the trees, there was the occasional glimpse of Lake Vidraru, but not much more – or maybe I was just too busy trying to keep out of the way of the large and heavily laden logging trucks, tonking their way down?

Between the trees, there was the occasional glimpse of Lake Vidraru, but not much more – or maybe I was just too busy trying to keep out of the way of the large and heavily laden logging trucks, tonking their way down? It was only after the map said we’d been following the shore for about 25km that we got to the dam and hydro-electric power station that created the lake, below a dramatic stainless-steel sculpture of a figure throwing lightning bolts about.

It was only after the map said we’d been following the shore for about 25km that we got to the dam and hydro-electric power station that created the lake, below a dramatic stainless-steel sculpture of a figure throwing lightning bolts about.

The main reason we’d come this far down the valley – almost back to Curtea d’Arges – was to find Poienari Castle. Built by Vlad Tepeș, you suddenly spot it atop one of the steepest rocks in the area. I don’t even want to know what it would have been like to visit back in the day – but today’s easy modern access involves 1,480 steps… Once you get up there, though, the views remind you just what a fantastic location this would have been for a fortress – totally controlling the route across the mountains between the then-independent kingdoms of Wallachia and Transylvania. The castle might be ruins today, but Vlad’s favourite hobby is celebrated by two firmly impaled mannequins outside the front door.  One of them bore a suspicious resemblance to Boris Johnson, but I think it might have been a coincidence.

One of them bore a suspicious resemblance to Boris Johnson, but I think it might have been a coincidence.

As we neared the end of the return journey over the pass to Cârța, we spotted another little old camper parked up, not far into the really steep bit of the climb and with the bonnet open. As we drew level, a quick “Are you OK?” thumbs up got a “Umm, not really” response – so we pulled in to see if there was anything we could do. It appeared that Josh & Carol’s Mazda Bongo had just got a bit hot and bothered, and decided to throw coolant all over the ground, but a quick check-over didn’t show anything seriously amiss. They decided to call it quits, though, and followed us back to the campsite. Another evening descended into nattering over dinner & wine…

The city of Sibiu next – another centre for the Saxon population, and with architecture that strongly shows this. The centre of the old town, spread over three main squares and closed off from the new town along one side with the remains of the old city wall and guild-built bastion towers, is very Germanic in look. The Evangelical cathedral was closed for restoration, but still dominated the place. Off to one side, legend says that the “Liar’s Bridge” will collapse if anybody goes onto it and tells a lie – strangely, it survived Ceașescu standing on it to give a speech… We didn’t bother with the Brukenthal art museum – it’s meant to be one of the best in the country, with a long roll-call of Old Masters – but the tickets weren’t cheap, even though a big sign pointed out that most of the big-name paintings were on loan to an exhibition elsewhere, and replaced with copies. The whole place was, to be honest, just a bit antiseptic and over-re stored for our taste.

stored for our taste.

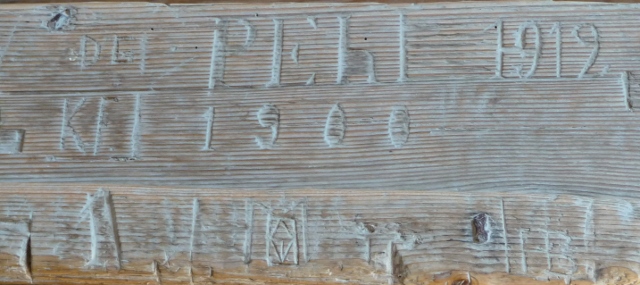

Sibiel, though, was much more like it. The church in the middle of the village is the home for another museum of glass-painted icons, set up by the village priest in the 1960s.

Most of the local homes had at least one of the icons, the work of local “naive” peasant artists and artisans. By displaying them in a museum, the priest reasoned, they would be available for many more people to admire, and to help understand this part of Transylvanian culture. The villagers decided he was right, and donated most of their icons, although some of them continue to visit the museum daily to pray to their original icon.

The priest, Father Zosim Oancea, had spent time in prison for activities deemed anti-communist, and had only just been released when he was posted to Sibiel – presumably, it was deemed somewhere quiet where he’d just disappear without trace or trouble… Not only did he start the museum, but he re-discovered the original 18th century frescoes in the village church, hidden under layers of whitewash. When we arrived at the museum, the friendly lady behind the ticket desk wasted no time in abandoning her post to give us a tour around, with the regional differences between the icons explained, in French. She was so enthusiastic about our tour that, when some Romanians followed us into the museum, she wasted no time in asking them if they also spoke French. Yes? Good, then you can join us…

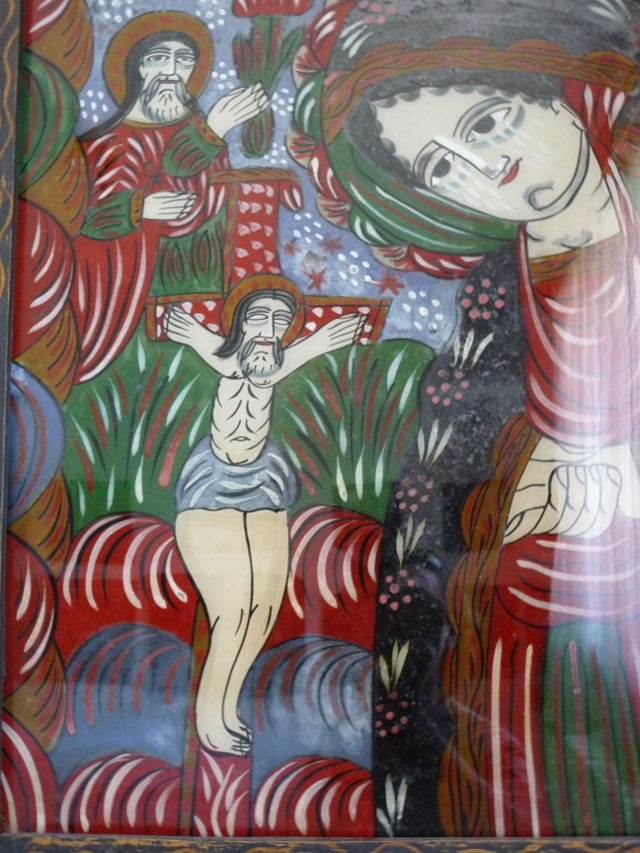

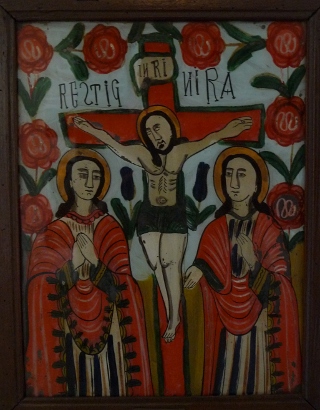

The biggest difference between an icon on glass and an icon on wood is that the glass is painted on the back – meaning the details have to be painted first, before the background colours, making fine detail much more difficult. Add in the self-taught nature of the artisans producing the icons, and the representations are much more naive and individual than most other works of art. They also reflect strongly the areas they were produced in, with variations in local costumes being shown. This was much more what we were wanting to find than the slightly sterile museum at Sambata had been!

The biggest difference between an icon on glass and an icon on wood is that the glass is painted on the back – meaning the details have to be painted first, before the background colours, making fine detail much more difficult. Add in the self-taught nature of the artisans producing the icons, and the representations are much more naive and individual than most other works of art. They also reflect strongly the areas they were produced in, with variations in local costumes being shown. This was much more what we were wanting to find than the slightly sterile museum at Sambata had been!